Is It Still "Impact" if Nobody Acknowledges It? - Part 2

Either way, I’m claiming a couple of things I did in 2023.

Last newsletter, I promised I would address a second question about impact:

2. What about when it was clearly you, but the force you “impacted” doesn’t declare the impact was yours?

Thinking about this question now, I might be asking it pre-emptively. It addresses a potential “impact” that I have been working towards, i.e., by paying attention to the direction of change (see my previous newsletter about impact vs prescience), and not one that has already taken place. In any case, let me have a go at answering.

For the whole period of the pandemic so far, I’ve held consultancies and policy and advocacy jobs in the international development sector. Disclaimer: to avoid giving the impression I’m speaking for any of my employers here, I’ll only ever discuss this work in general terms and only insofar as the materials I mention are in the public domain.

Anyway, during this time, I’ve written quite a few submissions to the Australian Government, calling on it to ramp up its investment in “social infrastructure”1 across its international development (“aid”) program in Asia and the Pacific. Why? Because our region’s developing nations have lacked the financial capacity to respond to the pandemic’s impacts by scaling up their social payments or retooling their public health and education systems. That’s what wealthy nations like Australia did when they shut their economies down.

Even now, as many of these developing nations grapple with how to return their economies to growth - and preferably inclusive growth - big questions remain about how they will improve the public systems that help equalise access to opportunity. Calls for donor governments like Australia’s to focus on grant-funded investments that help address these questions are therefore still highly relevant, and they will remain relevant for years to come.

Such calls also contrast with what the government has actually been doing since 2019. It briefly increased social infrastructure grant spending (see chart above), but only a little and only for a brief period during the worst years of the pandemic. Instead, it has poured much bigger money into loans for “hard” infrastructure, especially in projects that might thwart China from funding similar projects instead.

These loans are disbursed from the AIFFP, the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, whose debt financing approach the government’s own recent Development Finance Review (DFR) says is facing “a serious threat to [its] viability.” Why? Well, “due to rising interest rates and ongoing fiscal and debt challenges in many countries,” not to mention “the recent considerable increase in Australia’s cost of capital for lending.” These sound like pretty big and important concerns. I’m not sure if they’ll trigger any immediate changes to the AIFFP, however, as it seems responding to China remains the government’s priority for it.

In any case, whatever the AIFFP’s future prospects might be, reported recent changes by the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) suggest that donor governments are only going to double down on its debt financing approach instead of increasing grant spending on social infrastructure. Indeed, as if to signal these governments’ direction, the DAC has redefined “Official Development Assistance” (ODA, otherwise known as “aid funding”) so that it no longer consists only of:

“concessional [finance] (i.e. grants and soft loans) … administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as the main objective.”

Instead, as the ODA Reform Group has recently publicised, the definition now includes the following non-concessional forms of finance:

Lending to private actors at market terms without any budgetary subsidy;

Investing in commercially viable development projects that make substantial profits; and

Selling guarantees to banks on their loans to developing countries.

The Reform Group argues this change will allow donor governments to mask cuts to their “real” aid programs, i.e., which spring from their own efforts and money, and “produce meaningless, useless totals that serve only to mislead.” Assuming the group is right, this definitional change has also pulled the rug out from under the feet of advocates who argue every year for “more aid,” and whose rhetoric relies on the term “ODA” having a stable, unproblematic, meaning.

I guess advocates will need new arguments, perhaps which rely on new terms with more useful meanings. One option is to look at the “social infrastructure” figures to understand whether aid programs are funding the projects they actually value? If they do that, they could go back through the last few years’ parliamentary inquiries to find the submissions I’ve written and start using the arguments contained within them.

Back to the question then, of how do you demonstrate you’ve had an impact if nobody puts your name against it? My answer for now is it doesn’t matter. If advocates working on this issue update their language and methods, that’s fine by me.

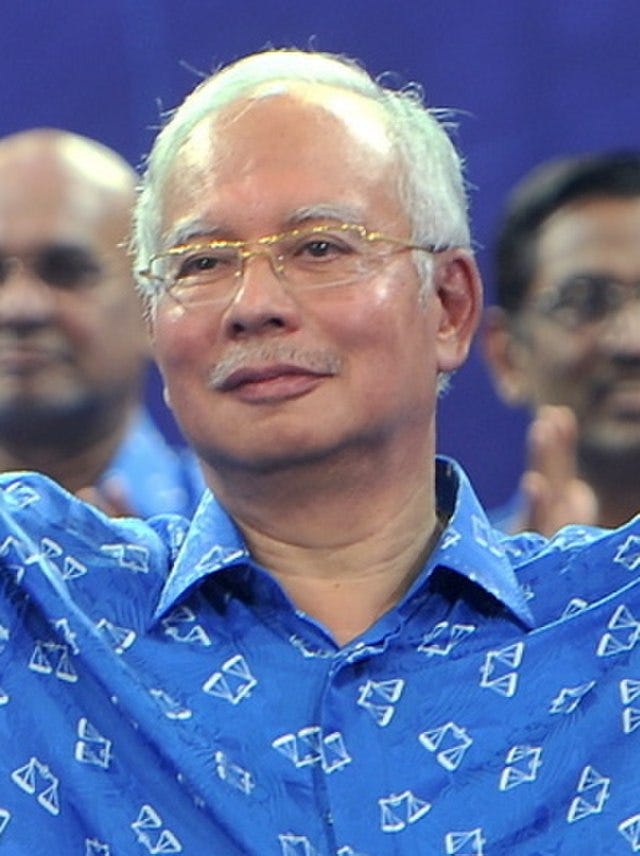

How to Understand the Latest Najib Razak Thing?

There’s quite a dramatic round of elite bargaining going on in Malaysia, as revealed by a recent decision to commute former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s prison sentence for his involvement in aspects of the 1MDB scandal from 12 years to 6. The decision has deeply disappointed activists and voters who want Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s “Madani” government to move more quickly to deliver democratic reforms. And yet it has also likely served as a means for Anwar to prolong his grip on power.

I’m too busy to write op-eds just now, but the sentence reduction should be understood as a gesture made in the context of several huge power negotiations that empower Anwar’s government in some ways, and constrain it in others:

Inside the government, between Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan and Zahid Hamidi’s UMNO (and whatever is left of UMNO’s Barisan Nasional coalition), which Pakatan needs to hold on to power in a coalition of frenemies. Najib remains influential inside UMNO, and it has called for him to be let off completely, so it’s been met half-way.

Between the government and the opposition coalition, dominated by the Islamist party PAS, whose rise has prompted commentators to call for a crackdown against it (which Munira Mustaffa and I recently argued against in The Diplomat). Several opposition figures recently tried, and failed, to orchestrate the government’s collapse at a secret meeting in Dubai, while for its part, the government has had several other opposition members sign statutory declarations supporting … the government. Foiled again.

Between the government and a group of political and business figures clustered around former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, including Mahathir’s children and his close associate, former Finance Minister Daim Zainuddin. Mahathir has issued several sharp statements during the multiple corruption probes now underway against this group, generally blaming minorities for the nation’s problems. Remember one brief period when he decided not to do that, and led the previous “Pakatan + frenemies” formation to victory for 2 years? I’ve got an article in The Round Table on that pretty artful campaign.

Between the government and Malaysia’s royal families, who share kingship between them under a rotating system. The outgoing King is the Sultan of Najib’s home state Pahang, and Najib is a member of that state’s aristocracy. Meanwhile, the new King, the Sultan of Johor, recently made it clear in an interview with Singapore’s Straits Times that he intends to play an active role in a lot of things.

In the middle of all this other action, Sarawak’s former Chief Minister Taib Mahmud - who used to have a courtyard named after him at the University of Adelaide - has allegedly been abducted from his hospital bed. This dramatic abduction was reportedly ordered by his much younger second wife, Raghad Waleed Alkurdi Taib, who is said to have all her household belongings packed up, ready to leave Malaysia as soon as he dies (although she has issued a statement denying everything). Taib’s children are suing their stepmother for allegedly transferring some of their family’s assets into her name - see the Sarawak Report for more reporting (and speculation).

The full term is “social infrastructure and services,” which the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) defines as “efforts to develop the human resource potential of developing countries in the sectors of education, health, population policies/programmes & reproductive health (further health & reproductive health), water supply & sanitation, government & civil society and other social infrastructure & services.”